As a high school math teacher, I run into plenty of obstacles: resistant students, anxious parents, not enough time or resources, and even my own burnout. When I hit a wall, I find it valuable to return to the question at the beginning of it all: What’s the best thing I can do to help my students grow?

It’s easy to repeat this mantra to myself, but that doesn’t always help me access its core meaning. Sometimes I can’t realize the meaning until I manifest it in my life, new and fresh. Manifesting meaning isn’t about reciting, but creating. It requires work, patience, and not-knowing.

This persistence and discipline could describe Zen koan study just as well as it describes teaching. In my experience, koans are a ready guide for a high school teacher.

I spent the better part of a month reading and rereading Case 52 of The Book of Serenity, entitled “Caoshan’s ‘Reality Body.’”

Caoshan asked elder De, “‘The buddha’s true reality body is like space: it manifests form in response to beings, like the moon in the water’ — how do you explain the principle of response?”

De said, “Like an ass looking in a well.”

Caoshan said, “You said a lot indeed, but you only said eighty percent.”

De said, “What about you, teacher?”

Caoshan said, “Like the well looking at the ass.”

Koans in The Book of Serenity are accompanied by a commentary from Wansong Xingxiu, a 12th-century Chinese Chan Buddhist monk — an ancestor of my school of Zen. Wansong introduces this one saying, “Those who have wisdom can understand by means of metaphors. If you come to where there is no possibility of comparison and similitude, how can you explain it to them?”

In the koan, Caoshan’s metaphor of “the moon in the water” symbolizes the realization that enlightenment isn’t something outside of us. The moon is reflected in the ocean, in lakes and streams, in puddles after the rain, in droplets of dew in the early morning, and even at the bottom of wells. Likewise, enlightenment is reflected in every drop of our lived experience. One of the key realizations in Zen is that when we meditate, we manifest the meaning of Zen. We become aware of the moon’s presence, having somehow doubted it before. And looking for it outside, we find it closer than we expect.

This koan probes me to ask myself, “What do you see when you look at your students?”

Enkyo O’Hara Roshi says a koan is “a form that obscures what it intends to communicate.” This seems unhelpful in the classroom. As teachers, our intention is to clearly and concisely communicate a specific subject. At the same time, we understand that a bare presentation of facts — historical dates, mathematical theorems, a list of an element’s properties — isn’t enough to communicate the meaning behind a subject. More often than not, the student will look at the majesty of a mathematical proof and ask, “So?”

That kind of comment can send teachers to the bar on a Friday afternoon, exasperated and shaking our heads. We peer into our wells and wonder if there’s anything down there.

I think part of the challenge of teaching math is that you are communicating to an audience about math, while simultaneously communicating how to be an audience for math. To paraphrase scholar and educator Magdalene Lampert on teaching fractions to fifth graders: you are teaching them how to be the type of people who talk about math.

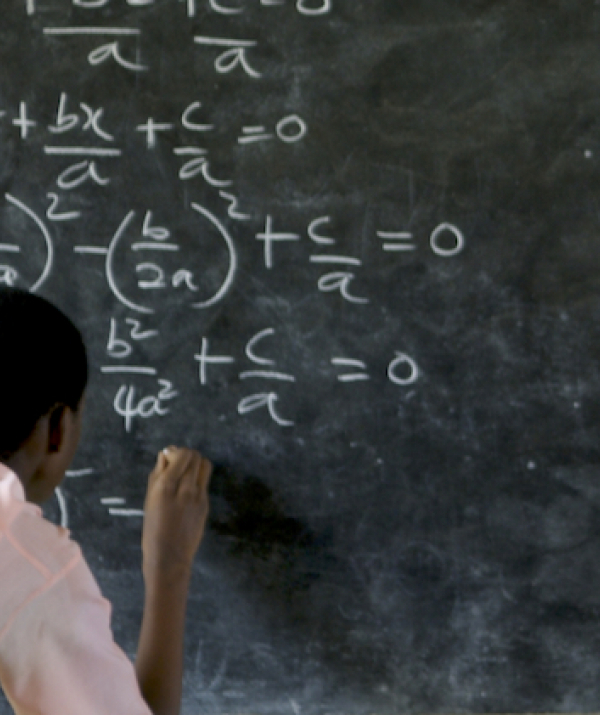

A math teacher doesn’t present proofs to an audience. Rather, a math teacher poses problems that have to be worked through. A problem is a form that obscures what it communicates, similar to a koan. In this regard, a good math problem is a koan for the student. Just as a koan is both a symbol of enlightenment and a means to realize enlightenment, so a math problem can be an expression of the problem and a means to solve the problem.

Among my students, not-knowing math seems to be the most shameful thing you can imagine. I remind them often that if they knew all of this math already, they wouldn’t have to be here. But they are here, and they’re facing what seems to be an insoluble problem. They work at it and it works at them, until suddenly the “problem” drops away and they communicate its meaning without speaking a word.

As teachers, sometimes we forget that this is what we’re trying to accomplish. Staring into the well, we think nothing will peer back. We throw up our hands and say, “The kids just don’t care!” And of course, at first, they don’t. Not now, not yet. We are in the business of cultivating people who care, who think, who create, imagine, argue, and collaborate.

I think the hard part about teaching—and about life—is that this is true for us, as teachers and as adults. We are always learning and growing, and every challenge that confronts us is a new koan, a new problem that obscures the truth of our lives. Working with koans and working with young people share this quality of resolving the insoluble. At the start, all you have is a jumble of words and feelings that you’re trying to convey.

What do you see when you look at your students? Wansong warns us against saying that we’re here to teach them. If I simply say, “I am here to teach,” then that isn’t a realization of my intention. In order to actually teach, I must do more than say I am teaching. I embody how to talk about math, and then how to observe and manifest its meaning. The meaning of math is communicated in every aspect of my being, and in every aspect of my students’.

With this understanding, I can turn to the next group of students, listen closely, and respond to them with a question or two. As we learn and grow together in this classroom, peering down the wells of mathematics, the meaning comes into view. How did I not see it there before?

Hoàn cảnh không quyết định nơi bạn đi đến mà chỉ xác định nơi bạn khởi đầu. (Your present circumstances don't determine where you can go; they merely determine where you start.)Nido Qubein

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ